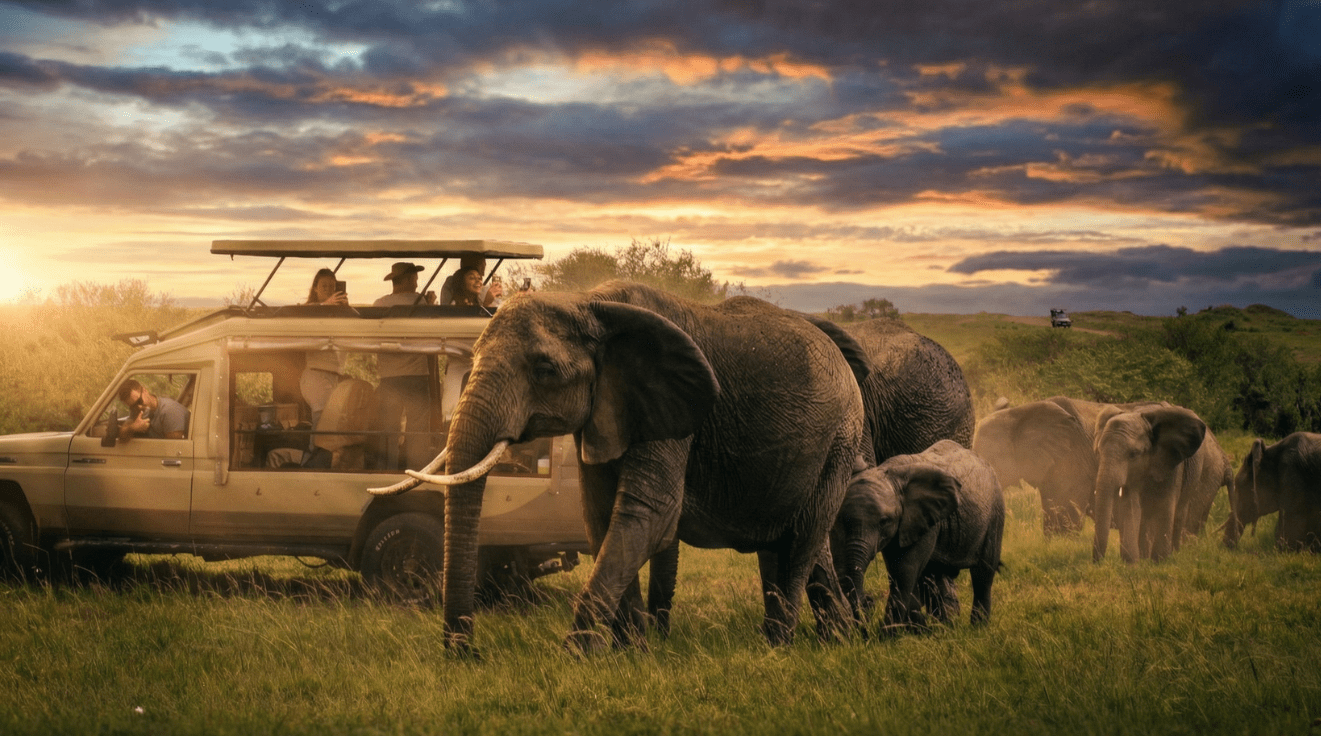

Do you have a death wish?” “Are you crazy?” “Did you make out your will?” These were all questions posed to me by friends, family, and neighbors when I told them I was off to South Luangwa National Park in Zambia to take a walking safari, where, instead of seeing wildlife from the relative safety confines of a tricked out Jeep, I would be traversing the grasslands on foot. Regular safaris – once you get past the initial excitement of seeing your first lion, zebra, leopard, rhino, or elephant in the wild – are safe (or at least safer as you are in the confines of a metal structure) but can be… challenging.

A normal day in a safari camp goes like this: Wake up at dawn, have breakfast, get in a truck and go find some animals for up to four hours. Return to camp, have lunch, take a siesta and go back out for an evening drive at around 4 p.m. During the evening drive, you will likely stop at some beautiful spot with expansive views of the sunset for a “Sundowner” – a drink next to the vehicle. This is usually the only point during the drive in which you are allowed out of the truck. After drinks are drunk and the sun has set, you re-enter the vehicle and try to spot night hunts, returning to camp around 8 p.m. for supper. Repeat this schedule for the next few days until you leave.

“I sink under the weight of the splendour of these visions! A wonderful serenity has taken possession of my entire soul, like these sweet mornings of spring”

At first, it is exciting. Visitors get to see every animal they’ve ever heard of or spied on the small screen.

But by the third day, seven to eight hours in a vehicle can wear on one’s patience. And the unimaginable happens – what was initially so exciting becomes quickly mundane. Especially if you don’t come across a pride of lions or any actual action.

Tips for Walking Safari

- Always start out early in the morning. In the mornings, the predators are presumable sated from catching and killing some prey the night before and trying to catch some sleep. Therefore, they are less likely to surround you and rip your throat out. This is a good thing.

- You can walk for as long as you like but should stop around 3 p.m. when the predators wake up from long naps and start to realize they might be hungry again. I ended up walking for around four hours every day and was happy to head back once the midday sun went into full effect.

- Wear muted colors

- Walk in a single file line. At the head of the line will be a guard from the National Park services who carries a rifle (just in case). Behind him is the head guide, the visitors and finally, another guide.

- Keep voices low. If you talk too loudly all the animals will run off.

- If you should happen upon a pride of lions (and we did) – stop. Group together and follow the guide and guard’s suggestion (which usually means be quiet and move slowly out of the way).

- Drink plenty of water. In the mornings it is cool but it heats up real quick! Dehydration is real and there’s nothing worse than being stuck out in the bush with dry mouth.

- Avoid all bodies of water – they are likely full of crocodiles and hippos.

- Be aware of what’s in the trees and the tall grass. Lions and leopards are masters at camouflage and often, unless you are a trained expert (which, thankfully, your guides are), you won’t notice them until you are literally on them. Or under them.

- While big cats may be the scariest animals, elephants, buffalo, and hippos are just as – if not more- dangerous. Keep a good distance from them at all times.

- Relax and have fun.

- The first day on foot was relatively calm. Fred led me through the bush and from distances I spotted impala, puku and other antelope, but it was more about what Fred called “behind the scenes.” He taught me how to identify scat – important signs to know where animals have been, what they are eating and if they are healthy – different trees, ground plants and other parts of the ecosystem. We went through a vast area of dead trees and stumps left over from the poaching in the 1970s and 1980s.

- “There used to be over 100,000 elephants and 4,000 black rhino in this park,” Fred said. “The elephants are very destructive. They will eat the bark of trees and rub against them until they fall down. However, through their scat, the trees get replanted. In less than ten years starting in 1976, 90 percent of the elephant population and 100 percent of the rhino population were wiped out but poaching and this area never recovered. It never got the chance to get replanted.”

King of the Forest

On the second day of walking, we hit paydirt. We followed a group of impala to a small herd of giraffe who allowed us to get relatively close. Suddenly, they galloped off and, in the distance, baboons started barking.

“Lions are near,” said. Ahead of us, in tall grass, a pride of lions was lounging, camouflaging perfectly into their surroundings.

The End

My heart was pumping. Our guard had his shotgun at the ready just in case, but it only had four bullets. There were five in the pride.

Following protocol, we silently grouped together, and slowly circumvented the pride.

It was thrilling. And fascinating. And as we made our way back to camp, we caught a herd of impala and zebra, walking single file, just like us, the other way.

It felt as if I had become part of the bush, part of the daily drama of life and death in the Luangwa crater. And that was worth it all.